In the sizzling symphony of a Chinese kitchen, few elements are as crucial or as celebrated as wok hei. This elusive term, often translated as "the breath of the wok" or "wok aroma," is the soul of a great stir-fry. It is that complex, intoxicating flavor and aroma that defines dishes from chow mein to Kung Pao chicken, a hallmark of culinary mastery that separates the good from the unforgettable. For centuries, it was the guarded secret of chefs, an almost mystical quality attributed to skill and a well-seasoned wok. Today, however, science offers a compelling explanation, revealing that this ancient culinary magic is, in fact, a spectacular dance of chemistry and physics, primarily driven by the Maillard reaction and caramelization under intense heat.

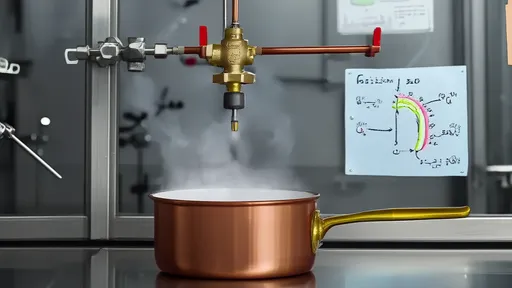

The journey to wok hei begins with the vessel itself. The traditional Chinese wok is a masterpiece of design, perfectly engineered for its task. Its rounded, sloping sides and wide surface area are not arbitrary. The shape allows for incredible heat distribution and retention. Made typically from carbon steel, it heats up rapidly and can withstand the terrifyingly high temperatures of a professional restaurant burner, which can roar at upwards of 100,000 BTUs—far beyond the capability of a standard home stove. This intense heat is the first non-negotiable ingredient. The wok is also designed for the constant tossing and flipping motion, known as bao, which is essential for the process. This technique ensures that ingredients are constantly moving, spending milliseconds in direct contact with the searing metal surface before being flung into the air to cool slightly, preventing burning while allowing for rapid, high-temperature cooking.

At the heart of this flavorful phenomenon lies a chemical process familiar to food scientists but magical to food lovers: the Maillard reaction. Named after the French chemist Louis-Camille Maillard who described it in the early 20th century, this is not merely burning food. It is a complex series of reactions between amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and reducing sugars when heated. This process generates hundreds of different flavor compounds, creating the deep, savory, roasted, and nutty notes we associate with grilled steak, toasted bread, roasted coffee, and, crucially, a proper stir-fry. In the context of the wok, the Maillard reaction occurs at a breathtaking pace. As thinly sliced meat, seafood, or even vegetables hit the scorching hot surface, their surfaces instantly dehydrate. The sugars and proteins within them then break down and recombine, forming a crust of new, flavorful compounds and that desirable brown color. The speed is critical; it creates the flavor without overcooking the interior, preserving texture and moisture.

Working in concert with the Maillard reaction is its sweet counterpart, caramelization. While the Maillard reaction requires amino acids and sugars, caramelization is the pyrolysis, or thermal decomposition, of sugar alone. When sucrose and other sugars are heated to high temperatures (around 170°C or 340°F and above), they begin to break down. They melt, foam, and undergo a series of chemical changes that produce a rich, complex, and slightly bitter sweetness alongside a deep brown color. In a stir-fry, this process is responsible for the sweet, nuanced flavors that develop in vegetables like onions and bell peppers, and it contributes to the overall flavor profile of the sauce. The combination of the savory, umami-rich compounds from the Maillard reaction and the deep sweetness from caramelization creates a foundational flavor base that is immensely complex and satisfying.

However, the chemistry alone does not fully capture the essence of wok hei. The physics of the cooking process plays an equally vital role. The technique of bao, or tossing, is what allows a chef to harness these chemical reactions without incinerating the food. With a flick of the wrist, the chef propels the ingredients upward. This momentary flight serves two purposes. First, it exposes all sides of the food evenly to the intense heat at the bottom of the wok, ensuring uniform browning and reaction. Second, and more importantly, it introduces oxygen and briefly lowers the temperature of each morsel. This brief cooling period is vital; it stops the cooking process from progressing from browning to outright burning, allowing for multiple cycles of intense heat application. This rhythmic dance—sear, toss, cool, repeat—is what builds layers of flavor without bitterness.

Furthermore, the design of the wok facilitates a fascinating thermal phenomenon. The center, or "hot spot," is where the most violent searing occurs. The sloping sides are progressively cooler. A skilled chef uses this gradient masterfully, pushing ingredients up the sides to simmer gently in a sauce or to keep warm while another element is blasted with heat in the center. This control is impossible to achieve on a flat pan. Finally, no discussion of wok hei is complete without mentioning the dramatic and purposeful ignition of fumes. When a liquid like soy sauce, rice wine, or stock is added to the searingly hot wok, it instantly vaporizes. These vapors, laden with oils and volatile organic compounds from the ingredients, can be ignited by the open flame, creating a brief but spectacular fireball that licks up and around the wok. This flash of extreme heat further catalyzes chemical reactions, adds a subtle smoky note, and is believed to be the final, defining step that imparts the true "breath" or "spirit" to the dish.

The pursuit of wok hei on a home stove presents a significant challenge. Standard electric or gas burners simply cannot generate the necessary BTUs to replicate the environment of a professional kitchen. The wok never gets hot enough to properly initiate the rapid Maillard reaction and caramelization, leading to steamed or boiled ingredients rather than seared ones. enthusiasts have devised workarounds, such as using a butane torch to supplement heat or cooking in very small batches to avoid cooling the wok down. Ultimately, the quest for wok hei is a testament to the beautiful intersection of art and science. It is a culinary tradition built on intuition and skill, now illuminated by our understanding of chemistry. It reminds us that the most profound flavors are often born from the most extreme conditions, a delicious paradox crafted in the fiery heart of the wok.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025