In the quiet corners of your kitchen, a silent, microscopic war is being waged. Your humble kimchi jar, crock of sauerkraut, or tub of fermented pickles is not merely a vessel for preserving vegetables—it is a dynamic, living ecosystem. Within its briny depths, trillions of microorganisms battle for dominance, engage in complex chemical warfare, and ultimately determine the fate of your ferment. This is not a peaceful coexistence; it is a fierce microbial conflict where only the strongest survive, and the spoils of war are the tangy, complex flavors we’ve come to love.

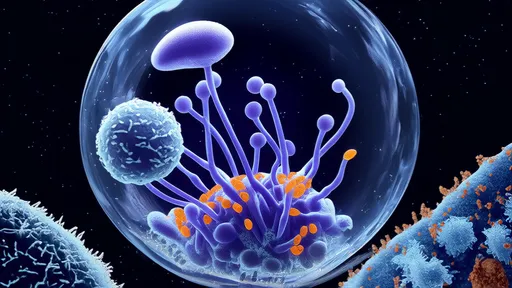

The initial stage of fermentation is a free-for-all. When you submerge vegetables in a salt brine, you create a selective environment. The salt concentration is high enough to inhibit many common spoilage bacteria and molds, but it is a welcoming haven for a specific group of salt-tolerant, beneficial microbes. At first, a diverse crowd of bacteria—both good and bad—from the vegetables, the air, and your hands are all present. It’s a microbial wild west. Leuconostoc mesenteroides, a hardy and relatively salt-resistant bacterium, often seizes the initiative. It begins rapidly consuming the sugars present in the vegetables, producing lactic acid, acetic acid (vinegar), carbon dioxide, and a range of aromatic compounds. This initial acid production is the first volley in the war, dramatically lowering the pH of the environment.

This acidification is a form of biological warfare. The increasing acidity creates an environment that is hostile, even lethal, to many of the undesirable microbes that could cause spoilage or produce off-flavors. Pathogens like E. coli and Listeria, which might have been present in small numbers, find themselves in an increasingly toxic bath of their own making, their cellular functions grinding to a halt. The carbon dioxide produced by Leuconostoc also helps by flushing out any residual oxygen from the jar, creating an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment that further suffocates molds and yeasts that require air to thrive.

But Leuconostoc's reign is short-lived. It is a moderate acidophile—it likes acid, but only to a point. As the pH continues to drop due to its own metabolic activities, it eventually creates conditions too acidic for its own survival. This is the critical turning point in the microbial war. Just as its population begins to decline from self-induced acid poisoning, a new, more acid-resistant warrior rises to prominence: the Lactobacillus genus.

Species like Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus brevis are the true workhorses of the mid to late stages of fermentation. They are extremophiles, perfectly adapted to thrive in the high-acid, anaerobic hellscape that their predecessor helped create. They take over the battlefield, consuming the remaining sugars with ruthless efficiency and pumping out even more lactic acid. This solidifies the victory against spoilage organisms and drives the pH down to levels that are stable and safe for long-term storage. The environment becomes so acidic that it is effectively sterilized against intruders; the war is won, and a stable peace, maintained by the lactic acid bacteria, is established.

The entire process is a breathtakingly elegant succession, a microbial relay race where one group changes the environment to suit the next. This battle is not just about survival; it's about flavor development. The initial compounds from Leuconostoc provide complexity, slight sweetness, and effervescence. The Lactobacilli contribute the profound, mouth-puckering sourness and deep, savory notes. The specific strains present, influenced by everything from the type of vegetable to the temperature of your kitchen, create the unique flavor profile of each batch. Your grandmother’s famous kimchi recipe tastes different from your neighbor’s precisely because their kitchens host slightly different microbial armies, leading to different battle outcomes and thus, different flavors.

Understanding this hidden war empowers the home fermenter. The salt level is your first strategic decision—too little, and you fail to suppress the initial spoilage organisms, allowing them to win the war. Too much, and you might inhibit even the beneficial Leuconostoc, stalling the entire process. Temperature is your control over the battle's pace. A warmer environment accelerates the microbial metabolism, making the war swift and fierce, often resulting in a sharper, more aggressive sourness. A cooler, slower fermentation allows for more nuanced development of flavors as the microbial succession unfolds more gradually.

Even the simple act of submerging the vegetables under the brine is a tactical move. It maintains the anaerobic conditions that favor your lactic acid bacterial allies and suppress your oxygen-dependent fungal enemies. When kahm yeast (a common harmless but unwelcome invader) forms a white film on the surface, it is a sign that oxygen is present—a breach in your defenses that allowed a enemy scout to infiltrate. When a ferment goes truly bad—slimy, putrid, or moldy—it means the undesirable microbes have achieved a decisive victory, often because the initial conditions (salt, temperature, submersion) failed to give the good bacteria their necessary advantage.

So the next time you open a jar of pickles or scoop out a helping of crisp sauerkraut, take a moment to appreciate the incredible microscopic conflict that made it possible. You are not just eating a food; you are tasting the aftermath of a war. You are enjoying the victory feast of trillions of lactic acid bacteria, the triumphant force that secured your food's safety, its preservation, and its deliciously complex flavor. Your fermenting jar is a testament to the ancient and ongoing dance of competition and cooperation that defines life itself, all happening silently on your countertop.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025