In the lush plantations of Central and South America, a silent crisis is unfolding that threatens the world's most popular fruit. The Cavendish banana, the yellow variety that dominates global supermarket shelves, faces an existential threat from a rapidly spreading fungal disease. This isn't the first time the banana industry has confronted such a disaster—the very reason Cavendish became dominant was because its predecessor, the Gros Michel variety, was virtually wiped out by a similar pathogen in the 1950s. History appears to be repeating itself, raising urgent questions about agricultural monoculture and food security.

The Cavendish banana's vulnerability stems from its biological nature. Unlike most fruits, commercial bananas are seedless and reproduce asexually through cloning. Farmers propagate new plants by cutting and replanting shoots from existing banana plants, creating genetically identical copies. While this ensures consistent fruit quality and characteristics consumers expect, it also means every Cavendish banana shares the exact same genetic makeup. This genetic uniformity becomes a catastrophic weakness when facing disease—a pathogen that can infect one plant can potentially destroy them all.

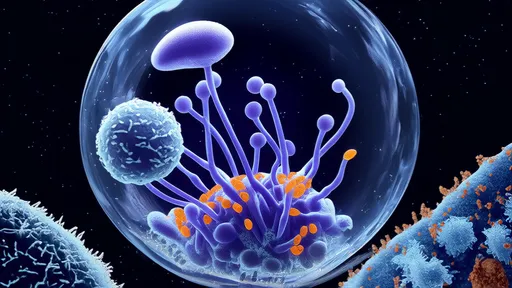

The current threat comes from Tropical Race 4 (TR4), a strain of Fusarium wilt fungus that attacks banana plants from the roots upward. First identified in Taiwan in the late 1960s, TR4 remained relatively contained in Southeast Asia for decades before beginning a global march that has now reached Latin America, the heart of commercial banana production. The fungus persists in soil for decades, making infected farmland unusable for banana cultivation. There are no effective chemical treatments, and because all Cavendish plants are genetically identical, none show natural resistance to the pathogen.

The situation echoes the mid-20th century banana crisis, when the previously dominant Gros Michel variety was devastated by an earlier strain of Fusarium wilt. The banana industry responded by switching to the Cavendish, which was resistant to that particular pathogen. This solution worked for half a century but created a potentially more dangerous situation today. The global banana industry has become more consolidated and dependent on a single variety, with Cavendish accounting for approximately 99% of banana exports worldwide and 47% of total global production.

Beyond the export market, the TR4 threat extends to food security in developing nations. While Western consumers might view bananas as a convenient snack, they serve as a crucial staple food and income source for millions of people in tropical regions. In some African countries, bananas provide up to 25% of daily calorie intake. The potential collapse of Cavendish production could have devastating consequences for smallholder farmers and local food systems that have come to depend on this variety.

Scientists and agricultural researchers are racing against time to find solutions. Approaches include developing genetically modified Cavendish bananas with TR4 resistance, cross-breeding with wild banana varieties that show natural resistance, and investigating soil management techniques that might suppress the fungus. Some researchers are even looking at using CRISPR gene-editing technology to create resistant strains without introducing foreign DNA. However, each solution faces significant challenges, from technical hurdles to public acceptance and regulatory approval.

Meanwhile, some experts advocate for fundamentally rethinking banana cultivation by promoting greater genetic diversity. There are over a thousand banana varieties worldwide, many with unique flavors, textures, and resistance qualities. Promoting alternative varieties could create more resilient agricultural systems. However, transitioning to new varieties presents economic challenges, as it would require changes to infrastructure, supply chains, and consumer expectations about what a banana should look and taste like.

The banana industry itself is taking defensive measures, implementing strict biosecurity protocols to prevent the spread of TR4. These include disinfecting vehicles and equipment, controlling movement of personnel between plantations, and using clean planting material. While these measures can slow the spread, most experts agree they cannot stop it indefinitely without a genetic solution to the Cavendish's vulnerability.

Consumer awareness and behavior will play a crucial role in shaping the future of bananas. As shoppers become more educated about the banana crisis, they may become more open to trying different varieties that offer natural disease resistance. Some specialty markets already offer alternative bananas like the Apple banana, Red banana, or Plantain, each with distinct flavors and culinary uses. Wider acceptance of diverse banana types could help create market incentives for growers to cultivate multiple varieties rather than relying solely on Cavendish.

The predicament of the Cavendish banana serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of monoculture in modern agriculture. From coffee to chocolate, many of the world's favorite foods depend on genetically uniform crops that are vulnerable to diseases, pests, and climate change. The banana crisis highlights the tension between the efficiency and consistency demanded by global food systems and the biological resilience that comes from genetic diversity.

Looking forward, the fate of the Cavendish banana remains uncertain. While complete extinction is unlikely—the variety will probably persist in some protected areas or through small-scale cultivation—its dominance of the global export market appears increasingly threatened. The coming decades will likely see a transformation in how bananas are grown, distributed, and consumed worldwide. Whether this transformation occurs through planned adaptation or catastrophic collapse may depend on actions taken today by researchers, industry leaders, policymakers, and consumers.

What remains clear is that the humble banana, often taken for granted as a simple fruit, actually represents complex intersections of biology, agriculture, economics, and culture. Its potential disappearance from supermarket shelves would represent more than just the loss of a popular fruit—it would signal the vulnerability of our global food systems and the urgent need for more sustainable and diverse agricultural practices. The story of the Cavendish banana serves as both warning and opportunity—a chance to rebuild our relationship with food on more resilient foundations.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025